Mozart writing the magnificent Overture to his opera Don Giovanni in just three hours after a night out. 20-year old Bill Gates programming for weeks on end to create the personal computing gateway. Alex Honnold climbing the sheer 1km El Capitan cliff-face without ropes or any support.

These are genius examples of a psychological state that underpins peak human performance in any arena. Without knowing what it is, or how to describe it except as being in the zone, many of us will have experienced it doing something we love: flow.

Flow is a period during which all we sense, all we feel, all we know, is what we are doing. “Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost,” is how flow is summarised by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, the Hungarian-American psychologist who first theorised and researched it in the 1970s. Simply, it’s a state of total concentration and pure focus.

Flow state changes

Neuroscience and psychology research over the past 15 years has built on Csíkszentmihályi’s work, giving deeper insights into this phenomenon. In flow our brain waves change. We actually use less of the brain: although the largest and most complex part, the neocortex, amps up, the prefrontal cortex, which regulates our thoughts, actions and emotions, switches off. And a number of neurochemicals and hormones are produced, including dopamine, serotonin and endorphins – referred to by neuroscientists as the happy chemicals.

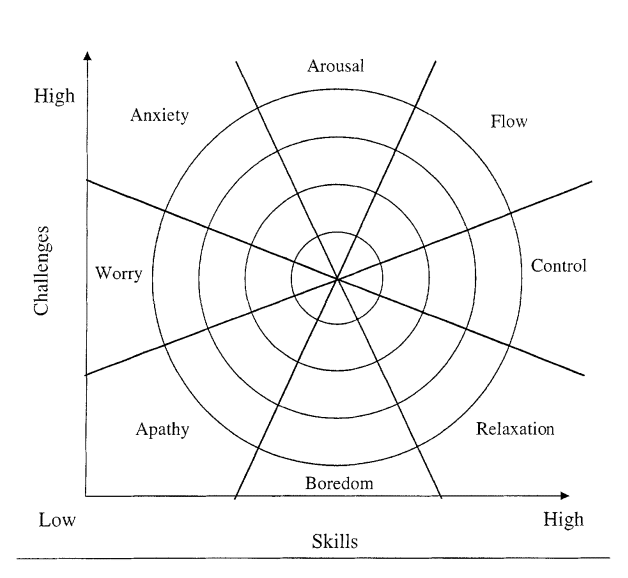

Discoveries have also been made about the key relationship at play during flow: the ratio of a person’s skills to the challenge they face. (See the diagram below.) When the challenge is too difficult by far for the skillset our psychological state veers towards anxiety; an easy task leads to relaxation and inattention. The sweet spot – different for everyone, but roughly at a 4% greater challenge differential – is where we click into precisely the right balance between pressure and belief, the edge of what we know and the subconscious desire to go beyond it.

These neurobiological and psychological changes cause specific characteristics to be present in the state of flow.

Self-confidence soars. That questioning voice in our head, kindling the fear of failure and sense-checking our initiatives, is silenced. We become too focused on doing to notice it, and, in a positive feedback loop, the conviction of our doing feeds further action. And, all the time, we feel in control.

We get ‘high’. The happy chemicals make a flow state addictive. This explains why surfers stay in the water for hours, gamers play online for an entire weekend, and why marketing and advertising professionals camp in their offices for days, hooked on ideation and crafting.

Time falls away. Involuntarily, we are absorbed and engaged – fascinated, focused, and, in a broad sense, having fun.

How flow improves performance

These changes improve performance in multiple ways. The pleasurable nature of being in flow brings an intrinsic motivation to the pursuit. Wholehearted commitment and full engagement is the impetus for deep learning, and the flood of specific chemicals enables our minds to recognise patterns and make new, creative and lateral-thinking connections faster. Constraining thoughts of possible failure are switched off, making us freer to experiment.

The performance gains of flow can be summarised in two ways. A particular challenge or activity may require the utmost concentration on one problem, or multitasking on many; it may need a series of rapid and critical decisions, or an intricate but gradual progression to one defining moment; it may be a combination of all. Flow allows for, because it is, the adaptive agility to take on any of these situations.

Secondly, flow is a representation of mastery – or, if the person isn’t yet at that level, it quickens their journey to mastery.

An example of what this agility and mastery looks like in terms of its heightened performance is in Walter Isaacson’s book about the early computing technology trailblazers, The Innovators. It includes a section on the young Bill Gates. At college he would stock up on pizza and caffeinated drinks before shifting into a cycle: study for 36 hours straight, sleep for 10, repeat. In his third term at Harvard University he and Paul Allen adopted this work pattern for a full two months to write the core code for what became the world’s pioneering and predominant personal computer software product suite. (Gates never completed his undergraduate degree at Harvard, because soon after that marathon coding session he dropped out to co-found Microsoft with Allen in 1975.)

This kind of work tempo is only possible in a state of flow. But what’s especially interesting about this story is the deliberateness with which Gates embarked on getting into flow. It illustrates that although flow is something of a paradox, because to shift into flow we need to abandon ourselves to the activity so that we stop overthinking and disassociate from pressures, the process of initiating flow can be planned.

This means that, as individuals, if we do the work to discover our personal triggers that catalyse it, the flow mind-state becomes repeatable. For violinist and concert-master with the Oregon Central Symphony, Diane Allen, these triggers are a passion to share her love of music and the thrill of being part of the orchestra’s 100-strong team. “Sharing is how I shift into the flow state on purpose,” she says, “and unity is how I shift into it with purpose.”

How companies can foster flow at work

Allen’s understanding of and ability to tap into her personal catalysts illustrates the importance of passion and purpose for individuals to shift into flow. More broadly, and relevant for organisational leaders and managers, the range of psychological and external factors that spark and facilitate flow can be stimulated within the workplace. There are five major considerations:

1. Set challenging goals. Corralling teams around a shared purpose is a foundation for flow. But it also requires a challenge-to-skills ratio that weighs towards a degree of struggle. This means, for instance, that high potential executives in particular should be tested, even pushed. (And if you are highly ambitious, you need to test and push yourself.)

2. Encourage risk-taking. High consequence is an external activator of flow, because it forces us to be attentive – to focus, one of the major characteristics of flow.

This has implications for employees responsible for innovation, as one example. When risk is not promoted, flow is denied, and the level of creativity unleashed by flow will not happen. This thinking is why the principle of failing forward – acceptance of failure as a building block towards success – is understood as critical for entrepreneurship and innovation.

3. Design roles and jobs that play to people’s strengths. An individual’s strongest attributes and capacities, when applied and developed into skillsets, are their most authentic and energising assets. When applied to work, they are most likely to be utilised in flow.

4. Assess physical spaces. Is it surprising that from around 1990 labour productivity growth in the U.S. started to fall well below its long-term average, simultaneous to the trend of significant reduction in the measured office space per employee? Correlation is not causation; still, studies now cast doubt on the claimed benefits of densely packed open plan offices or tiny cubicles. From the point of view of enabling flow, although the mind-state is feasible in cluttered or noisy environments, the intense concentration of flow usually happens when ambient distractions are minimised. If certain employees or teams are required to perform with absolute focus, think about whether the company’s spatial design is appropriate.

5. Allow autonomy. The autonomic nature of working in flow – subconscious, near effortless – means that it only happens when we want to do what we are doing. Giving employees responsibilities that they fully buy into, then allowing them to be in control, is a prerequisite for flow.

Practical matters

Some projections of how flow should manifest in organisations bring to mind idealistic workplaces. But in reality the vast majority of companies operate with all the flaws that come with busy, pressurised people and group dynamics.

Nevertheless, flow is recognised and applied by many leading companies. For outdoor gear manufacturer and retailer Patagonia it is integral to their brand proposition and corporate culture. The company’s website carries stories, linked to nature, of the wonderful feeling of flow, and its work-hours policy is longer weekday stretches followed by 3-day weekends. Another example is global business consultancy EY’s work-life harmonisation programme called It’s Yours to Build, which allows and encourages employees to personalise their work by allocating time to growth initiatives of their own choosing.

Actually, any organisation that inspires its employees to fuse their passion into their work is tapping into the idea of flow. Csíkszentmihályi’s original studies showed that flow can be triggered by work as well as play – this is what Patagonia has been doing overtly since its founding 50 years ago, and companies like EY and Google are attempting to do in a more nuanced way as part of the current interpretation of humancentric, frictionless work.

On an individual level, being able to shift into flow is a super-skill, an aggregation of many of the various soft skills that are now recognised as vital to performance and progression in the modern workplace.

So, do you want to get into the flow? Ask yourself this: What are my flow triggers, and how can I bring them to work?

From general business leadership to specific business skills, DigitalCampus has a spectrum of short courses designed to improve peoples’ productivity and prospects. Contact us today.

Managing Executive

DigitalCampus

In partnership with Dave Gorin

DigitalCampus is part of the LRMG group, specialists in igniting the performance of people.

Endless opportunities with continent’s most recognised

university and international university partners